Hardware Marathon: Installment 7

This post is the seventh in the series, “The Hardware Marathon.” In this series, I discuss the process involved in developing a hardware product from concept to production.

Our runner just passed the 19th mile marker in the marathon. More miles lie behind than ahead, but the race has taken its toll on the body. Exhaustion and boredom have crept up and the legs have begun to get weary. Doubts that the runner will ever see the finish line adds to the mental battle.

As the Beta version begins in product development, there may be a mixture of emotions ranging from frustration to hope. Like our runner, you may start to question if you will ever reach production. Worries of dwindling finances and fears that you’ve wasted a lot of time and money for something you’ll never achieve may invade your thoughts. Take heart! Just as the runner keeps putting one foot down in front of the other, keep going as you are closer to being done than you are to starting.

Image by StockCake

hurry up and wait

The Alpha phase was full of activity – designing, prototyping, testing and iterating to a refined manufacturable product. As you start Beta, you make (hopefully) one final set of minor changes and, thanks to the Supply Chain Detour, engage your production suppliers to make the first run of custom piece parts.

The Beta phase is full of waiting:

- Waiting to get in the tooling queue

- Waiting for the tool to get cut

- Waiting for the tool to be assembled and tested

- Waiting for all the parts to be delivered

- Waiting to get into the queue for laboratory testing

- Waiting for the testing to be completed

- Waiting for the test results

All of this waiting could be several months and that doesn’t account for the actual processing time.

While you wait, however, there is still much to do:

- Answering questions from the suppliers about the designs and updating drawings to better clarify the part requirements.

- Evaluating each part as it is delivered against the drawings and how it functions in the system compared to the prototype parts.

- Creating assembly documentation for production staff to use during Pilot.

- Developing production test stations for the parts to be tested before shipment.

- Finalizing the bill of materials and ensuring all the documentation is complete and accurate for your contract manufacturer.

- Negotiating your manufacturing contract.

Everything in Beta is done with a focused eye on manufacturing.

Supplier and tooling qualification

Once the engineers are confident in the design, it should be locked, meaning no more changes are allowed. This is necessary for production tools to be ordered. After the suppliers have reviewed the designs, they may request some minor accommodations for their specific manufacturing process. When agreement is reached on the design, the files are updated for the manufacturer to begin their process of fabricating tools and subsequent parts.

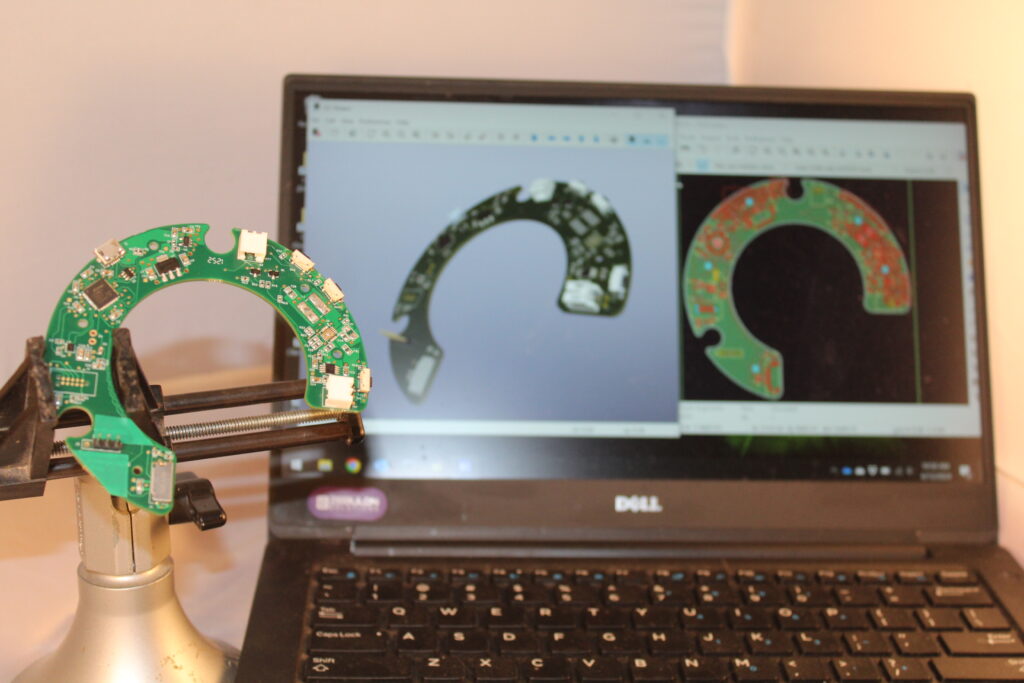

The fabrication process may require specific tooling, machine set-up, customized process, or a unique recipe. Whatever is involved, the first parts fabricated will need to be evaluated against the requirements to ensure compliance. The supplier should provide you samples after every modification for buy-off and buy-off should only be given when the parts meet the agreed upon requirements.

A word of caution: While the supplier should have their own quality control processes to evaluate parts, you should take time to measure, check, and inspect the parts to confirm they are fabricated as expected and function with the other parts as desired. It is not uncommon to find areas that are out of tolerance or don’t quite work right. The tool and/or design may need to be tweaked before final approval is given. Since these are the parts that will be used for production until the next redesign, you want to be sure they are as accurate as possible and function within the system.

Tracking changes

Since we mentioned that there could be changes going back to the supplier, it is a good business practice to document each change through a revision. Excellent business practices include capturing the history and status of every change. It is important to know what ‘version’ of the design you are approving with the supplier. This practice not only applies to specific parts, but the entire bill of materials (BOM) of the system. Since the BOM will be utilized by the contract manufacturer, documenting the supplier and associate part number as well as the quantity used in each system is necessary to ensure the right parts and the required number are available for production.

One note about the BOM: it needs to include every part in the system. Every part includes screws, nuts, tape, epoxy, and labels. As was mentioned in the Alpha blog, a complete BOM is important for not only ensuring all the parts are ordered, but to capture the costs of the product.

More testing…

In Alpha, we looked at the structured testing process of “EVT.” In Beta, many of the same tests are completed and referred to as “DVT” or Design Validation Testing. The focus of DVT is to validate the design of the product. While EVT may have tested just a few parts, DVT is most useful when it tests a statistical quantity. We recommend at least 10 parts per test to capture part variation, but 30 is even better if the time and resources allow.

“You want to capture variation so when you get into production, you’re not surprised. If you get one part failing out of 30, do something about it. If you are making 10,000 parts, 3% defects could be costly.”

In some industries, DVT is a formal process that involves laboratory certification. For the regulated industries, there will be standards that the product must meet in order to service that specific industry. They may have requirements around environmental performance, drop testing, flammability requirements, or emissions of Electromagnetic Interference (EMI). The standards can read like a legal book, and experts in the industry can help provide guidance on what tests and certifications are necessary.

The goal of testing throughout the development process is to avoid surprises at this phase. While there is a cost associated with every change, the later in the development cycle changes are identified, the more they cost. The cost and risk of modifying a tool is much greater than adjusting a 3D print.

“Really what you are looking at coming out of Beta are no changes, or, extremely minor changes. If you have big changes, you’ll have to repeat Beta or possibly even Alpha again.”

getting ready for Pilot phase

In Alpha, your testing was focused on how well the design met requirements. In Beta, you are doing that to a lesser degree, but you’re looking at how well your tooled parts meet those product requirements. You’re exiting Beta when your tooling is qualified, you have your suppliers ready for the first production build and the design and your BOM are locked. Any significant design changes will need to be pushed into the next design version, when you start this process over again. Let’s acknowledge the product is finally ready for production! In the Pilot phase, you will have your first units manufactured on a production line and evaluate any impacts the assembly process has on the design.

~~~~

Our runner has passed the 22nd mile marker and broken through “the wall”. A feeling of nearing the end erupts internally. Running through a mental checklist is done: no injuries, staying hydrated, shoes are doing well, and the pace is on target. There are only 4 miles left to the finish line – Isn’t it all downhill from here?